How Michel Gaißmayer brought Günther Uecker into the “Empire of Evil”: To Moscow, to Moscow!

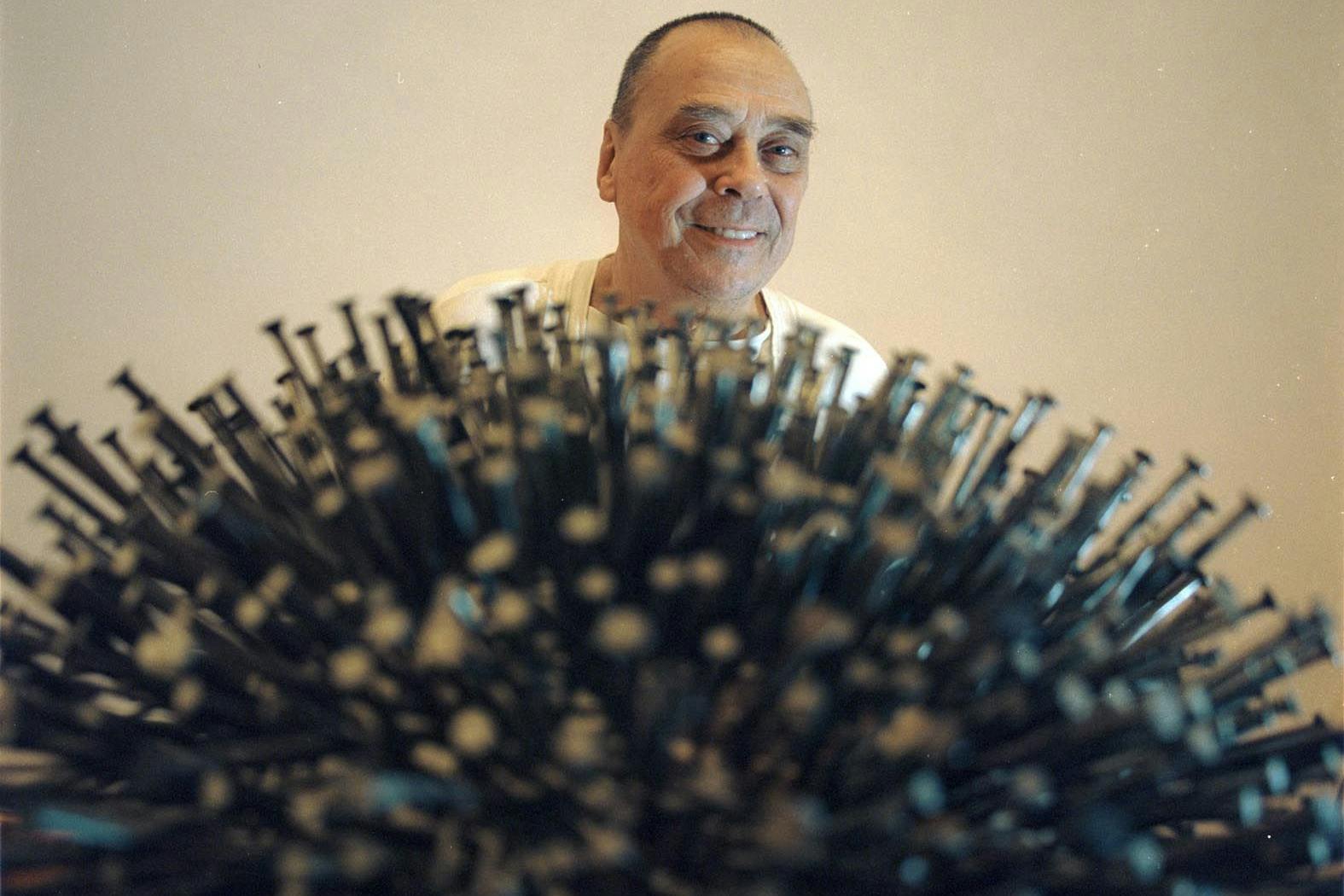

Michel Gaißmayer (1937-2025) was a member of Willy Brandt 's election campaign team in 1965, he brought Udo Lindenberg to thePalace of the Republic in 1983, and broughtGorbachev to Wim Wenders and the Bayreuth Festival before spending years dragging artists, scientists, and politicians in front of the camera of Alexander Kluge, the "screen hyena" (Heiner Müller). His main interest: to puncture the fronts and ideologies of the Cold War through art and cultural exchange. For example, with an exhibition in Moscow by the recently deceased nail artist Günther Uecker , one of the most important artists of the post-war period. This text is based on a conversation between Michel Gaißmayer and Stephan Suschke, which the latter recorded.

In 1988, I had an exhibition in Moscow with Günther Uecker. The starting point for this major undertaking was the event I had organized for Willy Brandt in Nuremberg in 1985: "Program for the Beginning." Günther Uecker had designed the poster for it, and, megalomaniacal as I sometimes was, I had said to him: "In return, I promise you a major exhibition."

He wanted one in Moscow. That was a very complicated and time-consuming situation. However, the foundations had already been laid with the aforementioned event. Bulat Okudzhava , who was speaking in the West for the first time, and Daniil Granin had come from the then Soviet Union. To avoid the story taking on the character of an international match, Granin had to talk about the destruction of Cologne, and Alexander Kluge about the destruction of Leningrad . Kluge spoke before the Russian program, Granin before the German program. Granin, who had witnessed the brutal destruction of Leningrad by the German Wehrmacht, did not find it easy to speak about the destruction of Cologne on the day of liberation in Nuremberg.

Two very important politicians from Moscow attended this event: Vadim Zagladin and Viktor Rykin. Rykin was the liaison between the SPD and the CPSU, and Zagladin was then the head of foreign policy in the Central Committee, Falin's predecessor. I gave these two the Uecker exhibition poster. They were happy about Granin and Okudzhava, and I said it would be great if we could hold an exhibition with Günther Uecker in Moscow. I also warned them that it wouldn't be easy, as Uecker's works were based on Malevich. And the axe with which not only abstract art was literally being hacked to pieces had been blazing in 1933 not only in the Third Reich but also in Stalin's Russia.

From the 1930s until Uecker's exhibition, there had never been an official exhibition of abstract art in Russia, even though the 1917 revolution in Russia had also been a revolution of art and culture. In both the visual arts and literature, an avant-garde emerged that was incredibly vibrant and diverse and strongly influenced Western European art in the 1920s. However, from the early 1930s onward, Socialist Realism, decreed by Stalin's henchmen, destroyed the plurality of art styles, the avant-garde. Many of these great Russian artists either fled, committed suicide like Mayakovsky, or fell victim to Stalin's terror.

I had been in Moscow regularly since 1978 and had many contacts. Among them was the Secretary General of the Artists' Association, Tahir Salahov, an Azerbaijani painter. There was a gallery in Cologne, Muschinkskaya, that focused on and exhibited the banned avant-garde in Russia. Salahov visited this gallery repeatedly. I visited Gerhard Richter's studio with him, and I asked the Wilhelm Hack Museum in Ludwigshafen to hold a Uecker exhibition, to which Salahov was invited. This is how I gradually prepared the exhibition in Moscow—you could also say, I foisted it on him.

Preparations lasted from 1985 to 1988, and the exhibition was repeatedly on the verge of collapse. One of the reasons, as so often, was money. Uecker said that Deutsche Bank would pay for everything. I asked the chairman of the board of Deutsche Bank, Friedrich Wilhelm Christians, for a meeting. I knew him because I had done the exhibition "War and Peace" with him. He said: "Gaißmayer, you can have everything: my experience, my contacts, but you can't get any money." So there I was, with all the commitments, but no money.

I went to see Richard von Weizsäcker, the then Federal President. I had a long history with Weizsäcker, which began with a conflict. It concerned an Arno Breker exhibition that was to take place in Berlin. I had organized the protest and agreed with the Senate that we would present the protest resolution, which had also appeared in the Tagesspiegel, along with the list of signatures, to Weizsäcker in Plötzensee on July 20, 1982.

Weizsäcker, then a completely disreputable figure in Bonn, became Governing Mayor of Berlin in 1981. He took over what the previous Senate had prepared. The then Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky was invited to the commemoration ceremony on July 20, 1982, in Plötzensee. I had told Kreisky that I would be there with Curt Bois, a well-known Jewish actor, to hand over the signatures to the Governing Mayor. We arrived when the microphones were already switched on. Weizsäcker knew who I was; he had been informed, but he asked who this strange old man was, with the microphone open. At that moment, Kreisky jumped up, hugged Bois, and said, "Curt, I was just holding your book."

Bois's memoirs had just been published by Henschel. Weizsäcker heard all of this, including that I had brought it on him, which earned me respect from him. I found it a magnanimous, almost noble attitude, very uncharacteristic of politicians, most of whom I have experienced as very vindictive. This respect led to him helping me secure two million Deutschmarks for the Uecker exhibition in 1987. He collected tranches of 250,000 Deutschmarks from various companies, raising the two million that the exhibition cost in total. Following Weizsäcker's plea, the Foreign Office donated half a million. The maximum amount they had previously sponsored was 20,000 for the Beuys exhibition "Coyote" in New York. Von Weizsäcker also assumed patronage of the Moscow exhibition and wrote the foreword for the catalog.

Michel Gaißmayer: An exhibition at the Intercontinental was unacceptable for meOnce we had the money together, Salahov, the chairman of the Soviet Artists' Union, explained to me that the exhibition had to take place at the Intercontinental Hotel. This was completely unacceptable to me because it would have meant that it would have been an exhibition only for foreigners paying foreign currency.

So I teamed up with Hans-Peter Riese, an ARD correspondent I knew personally, and his wife Michaela. I promised him a lecture for the parallel program to the exhibition. Riese had a personal interest in this: He had collected the banned abstract artists of Russia.

When it became clear that the exhibition would take place, all the established people who usually represented Uecker suddenly showed up, such as a gallery owned by Storms, which wanted to tie the exhibition project to itself. Finally, Hans-Peter Riese invited all the gallery owners and Uecker and his wife to his home for a giant bowl of caviar. He said: "If you push Gaißmayer out, Günther Uecker won't hammer a single nail in Moscow."

The Uecker exhibition was supported by the Friends of the North Rhine-Westphalia Art Collection. Its director was Werner Schmalenbach, a renowned art historian who had invested large sums of money to build the NRW Museum's art collection. Each of these objects was precious. Werner Schmalenbach helped launch the exhibition, but he did not live to see it. Prior to the show, the Friends organized a trip to Moscow, the goal of which was to show the fellow travelers Russian-Soviet contemporary art, the hallmark of the NRW Art Collection. This group of friends was flown to Moscow by Robert Rademacher, the VW representative in North Rhine-Westphalia. They were wealthy, well-to-do people from Düsseldorf and the surrounding area, such as Konrad Henkel's sister and the mother of the photographer Stefan Herfurth.

A social trip of millionaires to a Russian everyday tableAt that time, there were no exhibitions of avant-garde contemporary art in Moscow, but there was an underground scene. So I chartered Rafiks – a kind of VW bus, only much more primitive – that could accommodate a driver and six passengers. There were six or seven buses. These drove to the studios of individual artists, sometimes to an artist group. It was a round trip, but also an adventure. I was proud that these buses drove smoothly from artist to artist in a city where nothing worked. The same thing happened in Leningrad: an artists' carousel, a social trip of millionaires to a Russian everyday table that was no longer lavishly decorated. This not only earned me applause, but it also made Russia an interesting travel destination. As a result, some of these artists from Russia also came to North Rhine-Westphalia, set up camp there, and some stayed.

Since the issue of exhibition space hadn't yet been resolved, I went to the Central Committee of the CPSU. First, I went to Vadim Sagladin, to whom I briefly explained the problem: "You know this artist from Nuremberg. Now Salahov wants to hold the exhibition in just 400 square meters at the Interconti." Sagladin, who spoke perfect German, replied: "Okay, then I'll consult with him." At the same time, I presented the project to Raisa Gorbacheva, with whom I had a contact.

Suddenly, a representative of the Central Committee came with me to the Artists' Association, where I was given a 4,000-square-meter floor. I was lucky enough to know the gallery owner Hans (Hänschen) Mayer. He helped me keep Uecker in check, and we were able to agree on 100 paintings. They weren't hung on the walls, but displayed front and back. They stood in the room like this, which looked very beautiful, also because this arrangement gave the exhibition an installation-like feel and a very modern feel. It was the largest—I thought the best—exhibition Uecker had ever had.

I had done something that cannot be appreciated without having an idea of what Moscow's public buildings looked like in the late 1980s. Back then, practically everything had only one basic color: brown. I had found an old woman, Ludmila, who had helped me before. She painted the entire second floor of the building white. Suddenly, you could see pictures and objects on a white background, which made for a completely different experience.

Feast at the Interconti in aid of the Uecker exhibition

Hans (Hänschen) Mayer, the gallery owner, helped me tremendously. I asked him to bring me car tires. He did – he hung them around his neck at customs. And there was another nice story: Zurab Tsereteli, the president of the art academies of Moscow and Leningrad, had a great weakness for cars. The head of the artists' association, Salahov, had told me that Tsereteli wanted a Mercedes. Since I had secured Mercedes as a sponsor, they assumed that wouldn't be a problem for me. And it wasn't: There was a celebration at the Interconti to support the exhibition, and I gave Tsereteli the Mercedes. I placed a small model Mercedes on his table. Afterward, someone said to me: "It's a miracle that you're still alive."

Daimler-Chrysler hosted a huge reception. Edzard Reuter's deputy came to the opening in Moscow. It was customary there to pay bills immediately and in cash. As was also customary, there was a lot of drinking. Suddenly, Reuter's deputy said, "I'm running out of money here." "May I help you?" I asked. I gave him the money in rubles, which wasn't a problem thanks to the weak ruble exchange rate. But he resented that remark for the rest of his life.

What always preoccupied me was the question of how to promote such an exhibition. It's typical for exhibitions in Germany that they open, run, and then end with a closing event. But I always tried to make such exhibitions an event that went beyond the actual occasion, which in this case was more than just an art exhibition. I wanted to generate new attention every day, to embed the art in a cultural, political context. This was all the more important for an exhibition of unknown art like Uecker's, because it was the first time abstract art had been shown since the 1920s. That's why the Wilhelm Hack Museum organized a didactic approach to introduce people to this art.

In addition, there was an event every day: two lectures, two discussions with six or seven participants. Every week, artists such as Heiner Müller, Max Bill, Robert Wilson, Götz Adriani, Werner Spies, Pierre Restany, Germano Celant, and Hans Peter Riese participated in discussions, which generated great interest and further fueled attendance at the exhibition, thus also serving as advertising. There were film events where all the Soviet Union's avant-garde films were shown. And the films featuring Götz Friedrich Wagner productions, for which Uecker had designed the spaces.

Every week, artists such as Heiner Müller, Max Bill, Robert WilsonHowever, the problems with bureaucracy started all over again for the supporting program. Salahov was offended because he had been summoned to the Central Committee twice and repeatedly put obstacles in our way, even when it came to accommodating the high-profile guests. So the people from the Central Committee quickly said: Here is the old Central Committee Hotel on Plotnikov Street, the guests can be accommodated there. It was fantastic. It was on the Arbat. It didn't cost anything, and the telephone was also available. Communism. But no door could be locked. Also communism. Everyone, including Robert Wilson, was addressed as "Comrade". The supporting program kept the exhibition talked about for six weeks.

On the floor above us, there was a small exhibition by Francis Bacon—a magnificent artist. That's when I realized the difference between him and Uecker. I said to him, "Now you go upstairs and apologize." Bacon was upstairs, and a German nail artist was downstairs. If you know a little about fine art, it was disgraceful. Also, there wasn't a single review of Bacon's exhibition in the newspapers, while they were plastered with reviews of ours, which also led to us selling 20,000 catalogs, albeit at ridiculously low prices.

Because of the absolute shortage of materials in Moscow, a very large Uecker sculpture was dismantled after the exhibition by removing the nails and selling them to a building cooperative at a price per kilo.

However, something else caused me even greater difficulties: The equipment we had brought from Germany for the extensive supporting program of lectures and films was all stolen. This left me in a dire straits explaining to customs, because I could no longer export the missing equipment. The Central Committee saved me from the Lubyanka.

Guide for Chancellor KohlThe exhibition was a huge success – after less than four weeks, there had already been 250,000 visitors. The Chancellor also came. When Kohl visited Moscow, a visit to the Günther Uecker exhibition was part of his program. I guided Kohl through the exhibition with Werner Spies. Since Uecker hadn't received a special invitation, he was offended and didn't show up. Kohl was very attentive and genuinely interested. We were standing in front of two Uecker panels when Kohl said, "I know those, I've seen them before." I thought to myself: That can't be true. Then Kohl said something I'll never forget: "The older you get, the better your memory becomes."

He had actually seen these paintings before, at the Whitney Museum. At the end, Hannelore received two signed, 40-centimeter-long Uecker nails as a gift. Later, she proudly told me that she always carried them in her purse, and she showed them to me, too. At the end, Kohl asked how many visitors had seen the exhibition. I replied, "Over 250,000." He said there would be more than 300,000. There were only a few days left until the end of the exhibition, but Kohl was right.

Many years later, I met the director general of the West German Broadcasting Corporation (WDR), who was already retired at the time. Friedrich Nowottny was still angry with me for using the WDR's dedicated line for my calls all over the world. It was the only way for me to maintain contact. With a dedicated line, I could not only make calls from Moscow free of charge, but also without any problems, because the calls didn't have to be registered. Nowottny told me: "Gaißmayer, do you know what Kohl said to me at the end of his visit: I could never have imagined that a German communist would one day guide me through an abstract art exhibition in Moscow."

Kohl was a highly educated man, an intellectual with the mask of a respectable citizen. Kempowski told me that Kohl's library was located in the basement, and remarked admiringly: "Everything had been read." Another story: When Hannelore Kohl lost her mind, she turned on the faucets and made the library swim. You can't hurt an intellectual more than making his books unusable... Even if that was a made-up story, I believe it.

At the end of the exhibition, I realized that despite the great success, the artist was completely dissatisfied. Years later, I was sitting in the Breitenbacher Hof, the Adlon in Düsseldorf, and overheard two people talking at the bar. The artist had told them about the exhibition: Ten special planes would have had to be chartered to bring people from the West to see the exhibition. In reality, we had chartered a single plane, and no more than twenty people flew on it to the "Evil Empire."

This is an advance copy of the book "In the Gray Zone: Gaißmayer Tells," published this fall by Alexander Verlag Berlin. Edited by Stephan Suschke.

Do you have feedback? Write to us! [email protected]

Berliner-zeitung